Nowadays, finding out if you're pregnant is relatively easy — but it wasn't always that way. Over the centuries, people have come up with downright strange and sometimes revolting tests to figure out whether or not a person is knocked up. Some of them were useless, some required being a chemist in the bathroom, and some caused major ecological disasters.

Check out the long, strange history of pregnancy tests.

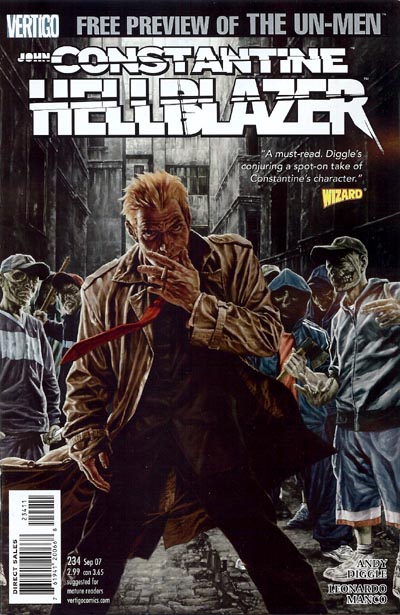

Top image: Carmen Seaby on Flickr.

The thing about pregnancy, as a condition, is most people eventually figure out their status on their own. Pregnancy tests, for much of history, have seemed unnecessary.

Still, people have always tried to find ways to peek inside themselves. Some people want to make an early announcement to family. Some need to put their names on a six-year-long waiting list for a private kindergarten, and hope that a year's worth of kids drop out of the running. Some just wish to experience the sheer joy of peeing on something scientific. Whatever the reason, all those who grab a stick and run to the ladies' room are participating in a long, occasionally-destructive, and sometimes outright loony march of scientific progress.

Flim-Flam and Hoo-Hahs

There were many ways said to spot a pregnancy early in ancient times, and they all revolve around various things to do with what is known in scientific circles as a woman's undercarriage. 'Babies come out of there,' the ancient wisdom seems to say. 'So clearly that's the first place to check.' The ancient Egyptians used to have a woman urinate on bags of wheat and bags of barley. If wheat sprouted, it was a girl. If barley did, it was a boy. If neither did, there was no pregnancy. (Incidentally, pregnant women's urine does make wheat and barley grow faster. Think about that the next time you dip into your whole grain cereal.)

The Greeks figured that they could check by applying perfumed linen to the genitals. The mouth and nose, they said, would take on the odor of the perfume if the woman was pregnant.

Medieval doctors, perhaps with a brief flash of insight or perhaps because they were fond of urine in general, focused their attention on liquid excretions. Any way of measuring urine, any way of mixing it with things, spilling it on things, and dipping things into it, became a way to foretell pregnancy.

Medieval doctors, perhaps with a brief flash of insight or perhaps because they were fond of urine in general, focused their attention on liquid excretions. Any way of measuring urine, any way of mixing it with things, spilling it on things, and dipping things into it, became a way to foretell pregnancy.

A needle put in a woman's urine would rust red or black, if the woman was pregnant. Sprinkled sulfur on urine would cause worms to suddenly appear, indicating pregnancy. Doctors even mixed urine with wine - thankfully just to observe its appearance. Since wine does react with certain proteins, this was as close as anyone at the time really came to being on the right track.

Rabbits and Frogs and Rats, Oh My!

To be fair, the medieval doctors' methods don't really sound sillier than anything that was used in the majority of the twentieth century. If someone told you that an injection of a pregnant woman's urine would make an adolescent rabbit horny, would you believe it? Doctors certainly wouldn't, which is why they got to horny bunnies by a roundabout route.

At first, early twentieth century scientists were simply doing what scientists are doing now; cataloging the seemingly endless amount of stuff that makes the human body go. Nowdays, this involves peering at DNA, RNA, and mRNA. In 1925, though, they trained their eyes on something a little bigger and looked at hormones. Hormones fluctuate in normal patterns, especially a roughly 28-day cycle that women go through when menstruating. Doctors followed this cycle of hormones. When pregnancy occurred, scientists found a spike in human chorionic gonadotropin hormone, or hCG, which could not be matched by any other biological state. In other words, they'd found something which, when measured, indicated pregnancy.

Next came the difficult task of finding a way to reliably and easily measure that something. What scientists came up with were bioassays, tests that required the use of biological organisms. Rats, naturally, were the first things on the chopping block. An injection of the urine of pregnant women into rats would send them into heat. A few days after the injection, these rats were dissected, in order to get the results. To keep the results from being skewed by naturally horny rats, scientists routinely picked rats who were too young to have gone into estrus yet.

Next up were rabbits, and they were by far the most famous of the animals, despite being used only briefly. The rabbit test has made it into many pop culture references. The phrase, "the rabbit died" came to imply pregnancy — although the rabbit died whether the woman was pregnant or not. The most infamous is the African Clawed Frog.

The demand for pregnancy tests in the thirties, moderate though it was, caused large amounts of frogs to be imported. With them, many people now think, came chytridiomycosis, a fungal disease that eventually managed to escape the lab, along with a few of the frogs. The fungus spread, and now threatens many of the world's amphibians.

The sad thing is, many of these tests were not reliable. Rabbits, rats, and frogs couldn't distinguish the difference between luteinizing hormone (LH) and the pregnancy-related hormone hCG unless the hCG level was sky high. The tests were expensive, and took days to run. The field was ripe for innovation, which came in the form of antibodies.

Immune Reactions and Peeing At Home

The first step away from heaps of dissected lab animals was taken in the 1960s, when science turned towards antibodies. In what were called immunoassays, rather than bioassays, hCG from the lab was swished together with anti-hCG antibodies and a urine sample from the woman. If the cells clumped in a particular way, the woman was pregnant. The test involved a lot of fiddling in a lab, but no animals and no long waiting period. Results were produced in a matter of hours.

Immunoassays were cheaper, and slightly more sensitive, so they overtook the bioassays quickly. One major deficiency was the old problem of luteinizing hormone. It was still mixed up with hCGs, and still caused false positives.

The way to solve that particular problem came in the form of more antibodies. (The immune system, it seemed, always had more to spare.) In the early 1970s, while working for the National Institute of Health, scientists found a special antibody. This antibody was directed at a subunit of hCG. The subunit of a protein assembles with the other proteins in a hormone to form the final product. This subunit was not to be found in LH, and so adding the specific antibodies for that subunit to the mix formed a new, distinct, pattern that indicated pregnancy and nothing else.

The way to solve that particular problem came in the form of more antibodies. (The immune system, it seemed, always had more to spare.) In the early 1970s, while working for the National Institute of Health, scientists found a special antibody. This antibody was directed at a subunit of hCG. The subunit of a protein assembles with the other proteins in a hormone to form the final product. This subunit was not to be found in LH, and so adding the specific antibodies for that subunit to the mix formed a new, distinct, pattern that indicated pregnancy and nothing else.

Once the science was done, consumer marketing took over. It took a few years, but in 1978, the first home pregnancy test started being advertised in women's magazines. It cost ten dollars. Included in the test kit was a vial of purified water, an eye dropper, a test tube stand with a mirror at the bottom that let you observe the patterns in the tube clearly, and a concoction of solutions that included sheep's blood. (One can't help but think the Medieval urinologists would approve.) The test was ninety-seven percent accurate for positive results, and eighty percent accurate for negative ones, provided it was used correctly. When the contents of a package include a tube of sheep's blood, it's a safe bet to guess it won't always be used correctly.

Researchers went to work finding simpler tests and reluctant bathroom chemists were soon relieved. The eighties saw the advent of one-step tests. The early nineties ushered in enzyme indicators. Now we have digital screens. We also have early testing capabilities. The norm used to be two weeks after the next menstrual period was supposed to start. Now testing can be done, with certain tests, eight days after ovulation. Results show up in minutes.

Researchers went to work finding simpler tests and reluctant bathroom chemists were soon relieved. The eighties saw the advent of one-step tests. The early nineties ushered in enzyme indicators. Now we have digital screens. We also have early testing capabilities. The norm used to be two weeks after the next menstrual period was supposed to start. Now testing can be done, with certain tests, eight days after ovulation. Results show up in minutes.

It still would be easier if the only thing necessary to do would be peeing on a bag of barley.

No comments:

Post a Comment